www.aljazeerah.info

Opinion Editorials, February 2021

Archives

Mission & Name

Conflict Terminology

Editorials

Gaza Holocaust

Gulf War

Isdood

Islam

News

News Photos

Opinion Editorials

US Foreign Policy (Dr. El-Najjar's Articles)

www.aljazeerah.info

How Oracle Sells Repression in China By Mara Hvistendahl Additional Reporting: Tatiana Dias and W. Paul Smith The Intercept, February 22, 2020 |

|

|

|

|

Oracle documents tout how its software can be used to integrate

social media activity with police data, including in Chinam, February 22, 2021 |

HOW ORACLE SELLS REPRESSION IN CHINA

In its bid for TikTok, Oracle was supposed to prevent data from being passed to Chinese police. Instead, it’s been marketing its own software for their surveillance work.

POLICE IN CHINA’S Liaoning province were sitting on mounds of data collected through invasive means: financial records, travel information, vehicle registrations, social media, and surveillance camera footage. To make sense of it all, they needed sophisticated analytic software. Enter American business computing giant Oracle, whose products could find relevant data in the police department’s disparate feeds and merge it with information from ongoing investigations.

So explained a China-based Oracle engineer at a developer conference at the company’s California headquarters in 2018. Slides from the presentation, hosted on Oracle’s website, begin with a “case outline” listing four Oracle “product[s] used” by Liaoning police to “do criminal analysis and prediction.” One slide shows Oracle software enabling Liaoning police to create network graphs based on hotel registrations and track down anyone who might be linked to a given suspect. Another shows the software being used to build a police dashboard and create “security case heat map[s].” Apparent pictures of the software interface show a blurred face and various Chinese names. The concluding slide states that the software helped police, whose datasets had been “incomprehensible,” more easily “trace the key people/objects/events” and “identify potential suspect[s]” — which in China often means dissidents.

Oracle representatives have marketed the company’s data analytics for use by police and security industry contractors across China, according to dozens of company documents hosted on its website. In at least two cases, the documents imply that provincial departments used the software in their operations. One is the slideshow story about Liaoning province. The other is an Oracle document describing police in Shanxi province as a “client” in need of an intelligence platform. Oracle also boasted that its data security services were used by other Chinese police entities, according to the documents — including police in Xinjiang, the site of a genocide against Muslim Uyghurs and other ethnic groups.

In marketing materials, Oracle said that its software could help police leverage information from online comments, investigation records, hotel registrations, license plate information, DNA databases, and images for facial recognition. Oracle presentations even suggested that police could use its products to combine social media activity with dedicated Chinese government databases tracking drug users and people in the entertainment industry, a group that includes sex workers. Oracle employees also promoted company technology for China’s “Police Cloud,” a big data platform implemented as part of the emerging surveillance state.

Several Oracle materials imply that the company has gone substantially further than marketing to Chinese police, which operate as part of the country’s Ministry of Public Security: One presentation detailing Oracle’s database and data security products contains a slide titled “Oracle and the national defense industry.” That title is followed by a list of multiple Chinese military entities, including the People’s Liberation Army, China National Nuclear Corporation, and China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. Defense entities are also the apparent target for two additional Oracle Chinese-language presentations, the most recent of which is dated 2015, and for events called the “People’s Armed Police Force–Oracle Cloud Computing Exchange Forum” and the “Oracle Xi’an Aviation and National Defense Industry Informatization Seminar” listed in Chinese on Oracle’s site. It is not known whether Oracle software is in use by any Chinese military entities or if the company has any agreements with them.

All told, the documents paint a disturbing picture of a tech company sacrificing its professed values to push its data analytics products in China, where the most formidable collector of data is the Chinese government.

Oracle’s presentations about China’s security apparatus raise a number of serious issues for the company, which is enmeshed with the U.S. defense establishment. It said last year that its customers include “all 5 branches of the U.S. military,” and it has recent or pending contracts with NASA, the Department of Commerce, and the CIA. Oracle has also worked closely with police departments in the U.S.

Oracle’s government work helped it and Walmart edge out rivals in a bid to control U.S. operations for the Chinese-owned social media company TikTok last year, after the Trump administration ordered TikTok to find a U.S. buyer for its American operations. The proposed deal, under challenge in court, was driven by concerns that TikTok’s Beijing-based parent company might pass on sensitive user data to Chinese authorities. But in a strange twist, the documents show that Oracle has marketed its software’s use by those same authorities in an extreme example of putting profit over human rights.

“Companies should not be selling any kind of surveillance predictive policing system to the Ministry of Public Security,” said Maya Wang, a China senior researcher for Human Rights Watch, who was among a group of experts that reviewed some of the presentations for The Intercept. “They should not have any business with the Ministry of Public Security. This raises questions about the role that the West has played in inspiring and building surveillance systems in China.”

“This raises questions about the role that the West has played in inspiring and building surveillance systems in China.”

In addition to human rights concerns, the documents point to profound national security questions. One of the military-oriented presentations cites Oracle’s U.S. defense work in an apparent effort to win Chinese cloud computing contracts. “The fact that an American technology company is marketing capabilities to increase the combat power of Chinese military is definitely poor judgment, especially given how avidly Oracle continues to pursue opportunities to work for the Defense Department,” said Elsa Kania, a fellow at the Center for a New American Security and an expert on Chinese military strategy, after reviewing the relevant documents. “It says something about the pursuit of profits and market share over questions of ethics and due diligence.”

In a statement to The Intercept, Oracle spokesperson Jessica Moore said the materials showed “what our products could do if others built on top of them” and were “aspirational business development ideas” that “do not indicate any targeted or intended sales/support execution.” The company is not selling data analytics software “for any of the end uses implied in the materials,” she said. “Such activities would be considered inconsistent with Oracle’s core Corporate Citizenship Values, including our Human Rights statement.”

She stated further that Oracle does “extensive due diligence” to ensure its exports comply with trade restrictions, including in any dealings with the Chinese military. Asked about Oracle’s apparent marketing to military-linked entities, she wrote, “Any such transactions would have to be in full compliance with U.S. and applicable export control and economic sanctions laws and regulations. Period. And beyond our legal and regulatory obligations, Oracle is VERY conservative and cautious in how we even approach such opportunities.”

Moore described the engineer’s story about the Liaoning police leveraging Oracle software as a “pitch deck” that was “theoretical” and said it “does not depict or demonstrate an actual Oracle implemented solution.” It would “require extensive third-party work to actually develop and implement,” she said.

A former Oracle senior director, Xavier Lopez, told The Intercept that marketing cases like the Liaoning police example are often presented at tech conferences to show developers how they can build custom software for particular industries or government entities on top of generic Oracle platforms. Lopez co-presented a similar Chinese police “use case” at the 2017 Oracle OpenWorld in San Francisco, a massive annual conference that draws some 60,000 attendees. The presentation indicated that an unnamed “Chinese Police Department” had used Oracle graph analysis software to home in on suspects by ingesting “documents, social media, web content, chat rooms, flight records, hotel stay registries, and publically [sic] available open datasets.”

Lopez confirmed that “the police province in China used the software to develop that,” referring to the data analysis described in the slide. “They just shared with us some generic information on how it was used.” He did not recall which province provided the information.

Moore said, of Lopez’s presentation, that “we have no known implementation with a ‘Chinese Police Department’” and that “the definition of ‘use case’ is very different than an actual, implementable product or service, which Oracle does not have.”

Lopez was clear that his presentation was not a hypothetical, however: “The data didn’t come from us. The data came from the province. The province uses the software, they license the software to use for different things, for different use cases. And this was one example of when they used it for that particular use case.”

Oracle got its start in the late 1970s building databases for the CIA and still fosters a reputation for being closely allied with the U.S. government. Co-founder and chair of the board Larry Ellison criticized Google’s 2018 plans for a censored Chinese search engine, telling Fox Business, “We have a serious competition going with China. I’m on Team USA.” The fact that Google “goes into China and facilitates the Chinese government surveilling their people is pretty shocking,” he added.

Oracle CEO Safra Catz, meanwhile, is a commissioner on the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, a Department of Defense-backed initiative that seeks to maintain U.S. dominance in artificial intelligence. A key interest of the commission has been China’s growing technological prowess, and in her role as a commissioner, Catz has received weekly email updates from the National Security Council’s former China director on the “malign behavior of the Chinese Communist Party.”

“The concern is that Oracle executives are determining U.S. national security policy and yet have simultaneously pitched technology to Chinese police for intelligence purposes,” said Jack Poulson, who resigned from Google in 2018 after The Intercept exposed the company’s search plans in China and is now executive director of the nonprofit Tech Inquiry, which monitors bias, human rights abuses, and financial flows at tech companies. “This is not the first such company, but this might be one of the most egregious examples.”

“The concern is that Oracle executives are determining U.S. national security policy and yet have simultaneously pitched technology to Chinese police for intelligence purposes.”

Oracle was cozy with the Trump administration, a fact that may have aided its TikTok bid. Catz was a member of Donald Trump’s 2016 transition team, and she donated $130,600 to Trump’s reelection campaign last year. But the fate of the TikTok deal may now be in Joe Biden’s hands. TikTok has been fighting Trump’s executive order in court, and the U.S. government’s response to the challenge is due today. It is unclear whether Biden’s Justice Department will defend Trump’s action. Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that the Biden administration had indefinitely shelved the TikTok-Oracle-Walmart deal. In the meantime, Oracle is still technically in the running to acquire a significant stake in TikTok’s American operations. Under the proposed terms of the deal, Oracle would host data from U.S. users that flows through the app as a lead investor in an independent company called TikTok Global. It would also be able to review TikTok’s source code.

Oracle’s interest in both TikTok and data-driven policing stems from its sustained push into the burgeoning cloud market and the related expansion of its artificial intelligence offerings. The company’s roots are in database software, but over the past decade it has acquired several online search and data analytics startups. Oracle has also become a major data broker. It claims to sell data on more than 300 million people around the world — what it calls “the world’s largest collection of third-party data.”

Its efforts are part of a global shift toward big tech entering policing, in which more niche companies like Palantir and PredPol are being edged out by large platform companies like Amazon, IBM, and Microsoft. Oracle’s data analytics software and applications have been used by the Chicago Police Department and the Illinois State Police, as well as by several local U.S. governments.

Under “Barriers to Overcome,” it lists “privacy protections.”

But Oracle has also marketed police applications of its software in countries with deplorable human rights records, including not just China but also Brazil, Mexico, Pakistan, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, according to company documents and police contracts uncovered by The Intercept, as well as apparent Oracle employee presentations uploaded to Slideshare and other sites. The documents make clear that the software could be used to further surveillance. One Oracle global marketing brochure from its website notes that police “need crime analysis and social media analytics in one source.” Another implies that Oracle’s software can help police filter 700 million messages a day from major social media apps — including WeChat and Weibo — as well as “chat rooms, forum pages, reviews and news media.” Under “Barriers to Overcome,” it lists “privacy protections.”

“We have a lot of evidence of the negative potential of this type of technology for the Black and outskirts population” in favelas and other poor neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro, said Pablo Nunes, a researcher at the Rio-based Center of Studies on Security and Citizenship. “It also reinforces the criminalization of certain spaces in the city.”

Some Oracle marketing materials claim that its technology can help officers prevent or anticipate crime. That’s a specious claim even in societies with strong civil liberties protections. In China, which lacks a free press and other means for civic accountability, police can use big data to justify basically any decision — most horrifically, the detention of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang. “Democratic systems generally have to answer some resistance and pushback from people who are being discriminated against,” said Wang, of Human Rights Watch. “But in China the police don’t have to answer to any pressures. So the very imperfect design of the system can just expand.” Oracle’s imprimatur aids in that growth.

Moore, the Oracle spokesperson, said the company’s global customers and end uses were “authorized” and that the company’s products are not specifically tailored to crime or surveillance. “Third parties or systems integrators could develop products on top of our technology,” she wrote, “and could be configured and implemented for such purposes but would need to involve extensive consulting/development of such systems.”

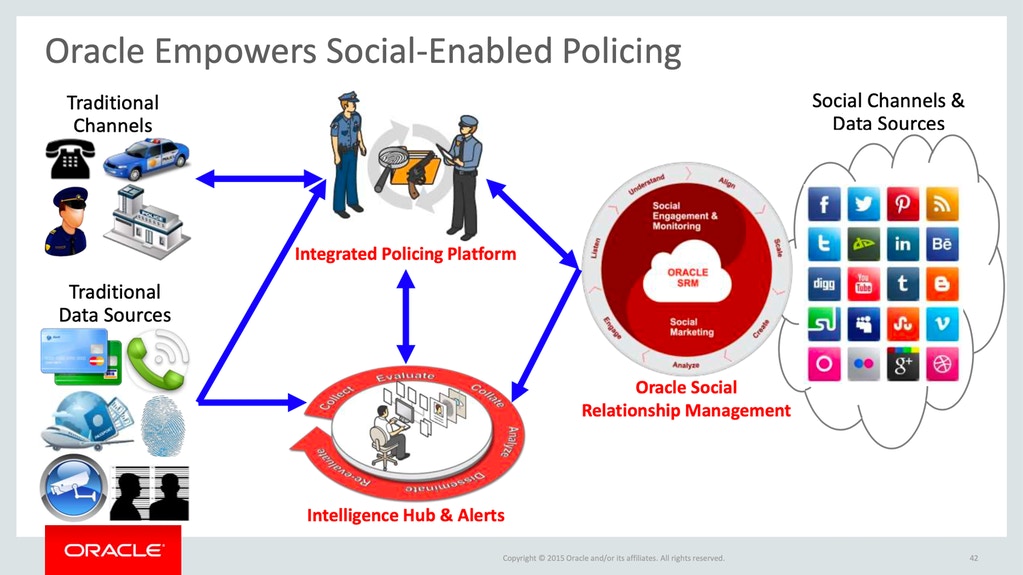

Integrated Policing

The Oracle documents uncovered by The Intercept span the period between 2010 and 2020. They broadly describe an approach called “social-enabled policing” or “integrated policing,” which entails merging traditional sources of police information with data from social media. The goal, according to one document, is to remove “barriers and stovepipes, facilitating a lifecycle 360-degree view of the victim, witness, suspect and incident” in order to police “both the physical and digital worlds.”

A prominent figure promoting this concept was Hong-Eng Koh, a former Singaporean police officer who worked at Oracle from 2010-2016, at least part of that time from Beijing. Koh is described in Oracle documents, an archived Oracle conference agenda, and his own and former colleagues’ social media posts as Oracle’s “senior director” or “global lead” for justice and public safety during that time. According to the documents, Koh oversaw a team of employees who approached government agencies around the world about police applications of Oracle’s software. Oracle’s Moore claimed that the company never had an “Oracle Justice and Public Safety group” but acknowledged there was a group of employees working with Koh. She added that Koh “was in a Global Industry Solutions role focused on positioning Oracle products with various industries, including Public Sector.”

Koh appears to be an enthusiastic fan of police work. “Which other job gives you a personal gun?” reads a post from what appears to be his LinkedIn account about his early days as an officer in Singapore. “For a few months, I felt so ‘empowered’ that whether on or off duty, I eagerly carried the gun and bullets everywhere I visited.” (Koh did not respond to multiple email and LinkedIn requests to comment for this story.)

At Oracle, he had other powerful tools at his disposal. In the documents, Oracle pitches a suite of analytics and enterprise software called Oracle Business Intelligence for police use, including in China. Such software has broad applications and is widely used by companies for business analysis. Lopez, the former Oracle senior director, said that while Oracle’s engineers generally don’t overhaul software like Business Intelligence for specific industries, Oracle does market it for specific uses. “When you market something, you want to have your marketing illustrate how this generic software can be customized or modified or tuned to solve your industry’s problems,” he said. He added that Oracle’s engineers would also often add features to software based on government or corporate input. A video on Oracle’s site titled “Transforming Justice and Public Safety” suggests close collaboration with police on integrating “siloed data into a single intelligence hub.” “We can help you build your ideal way forward,” it says.

Oracle is the world’s leading supplier of commercial database software, and for police departments already using the company’s databases, one advantage of Oracle’s analytics offerings is that they can more readily layer software on top.

The company documents reviewed by The Intercept note that countries have different laws governing the use of data-driven policing, but they brush over civil liberties concerns. “A law-abiding citizen should not be afraid,” reads the Oracle document on “social-enabled policing,” which lists Koh as a co-author. “If a person does not shy away [from] posting on social networking site publicly, he/she needs to understand that anyone, including marketing companies, government agencies and even criminals, can view such contents without his/her permission.” The document continues, the “Internet never forgets.”

The internet has not forgotten Koh. A Slideshare account in his name contains presentations detailing work with police departments around the world, and the LinkedIn account contains an apparent photo of Koh with the Pakistan Rangers, a paramilitary federal law enforcement organization.

Big Data and Repressive Regimes

Koh seems to have found a receptive audience in repressive regimes where authorities were sitting on massive troves of information. Over the past decade, Chinese authorities have strived to use big data to prevent incidents that threaten the Communist Party. Chinese President Xi Jinping has talked of preserving “stability” by guarding against “black swan,” or unforeseen, events. “The logic is that it’s no longer sufficient to react to events, because by then it’s too late,” said Edward Schwarck, a Ph.D. student at the University of Oxford who has written about the origins of predictive policing in China. “You need to preempt events.”

“The logic is that it’s no longer sufficient to react to events, because by then it’s too late.”

Over the past few 20 years, China has rolled out electronic IDs, real-name registration online, automated license plate readers, and checkpoints bolstered by facial recognition and surveillance cameras. “Everyone is using phones, using WeChat, using all these devices that can be tracked and that can generate a lot of data points,” said Daniel Sprick, a China legal scholar at the University of Cologne who studies predictive policing in China. Some data collected under the emerging social credit system feeds into information accessible by police as well, he added. “So police are in a position to have a unique data set of more or less everything they want to know.”

In Brazil, the government has been working tirelessly to merge information and create megadatabases of citizens. The country’s Citizen Base Register, for example, gathers more than 50 types of information about Brazilians, including employment details, health data, and biometric information, such as fingerprints and photos of people’s faces. Under the direction of President Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s Federal Police are also creating a unified data system that gathers biometric and crime data from all states in the country.

Authorities in the United Arab Emirates have similarly moved to amass data on citizens. In Dubai, police have rolled out a massive surveillance program called Oyoon, which literally means “Eyes.” The program, which involves 5,000 surveillance cameras, purportedly allows police to track people throughout the city by uploading a mugshot into a database.

Koh claims on the LinkedIn account that his team “successfully developed multiple industry solutions” for police in all three countries.

One Oracle-branded Slideshare presentation apparently posted by Koh describes a “big data analytics demo” involving police in the UAE. Technology helped authorities there more easily monitor suspects’ movements and phone calls, build networks of people who are working together, and identify individuals who happen to be near a suspect, it explains. One slide shows what appears to be an Abu Dhabi police mobile interface alongside a server.

Oracle documents support many of the Slideshare claims. In Mexico, one country where Koh claims to have brokered deals, an Oracle slide deck says that the company’s databases and middleware helped authorities conduct “real-time video intelligence” and license plate monitoring in partnership with the company iOmniscient, which does facial recognition, crowd behavior analytics, and “sound and smell analytics.”

In Rio de Janeiro, meanwhile, Oracle sold Business Intelligence, the data analytics software, to the Civil Police, which is known for its ties to drug rings and local mafia. Contracts with Oracle, which began in 2013 and renewed every year since, show that Rio’s police paid $500,000 per year for the software.

One of Koh’s Slideshare presentations includes an apparent photo of Koh with José Roberto Peixoto and Andre Drumond Flores, both senior information technology employees for the Civil Police. Drumond boasted to a researcher in 2017 that the police had an “Iron Man 3 machine.” The Oracle Exadata processor appeared in the photo and in a scene of the Hollywood action blockbuster. Drumond said that the system could help police find patterns of behavior and possible suspects in police data.

Oracle software has been marketed for police applications in Brazil, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates, according to company documents and police contracts uncovered by The Intercept.

But Koh seems to have made the deepest inroads in China. For the last two years of his tenure at Oracle, according to his professional bios and to his presentations, he simultaneously held a visiting researcher position at People’s Public Security University of China, China’s leading police academy. In addition to training officers and police officials, the school has labs that work on digital forensics and image recognition, technologies that help power the surveillance state. Asked about this, Oracle’s Moore wrote, “LinkedIn profiles should not be confused with actual work performed.”

Oracle in China

Oracle’s technology was used in key Chinese government surveillance initiatives before Koh came on board. Company documents boast that in the years before 2010, its technology was used to build the pilot for China’s grid management system, a network of neighborhood-level social monitoring and control, in Beijing’s Dongcheng District. The documents also claim that Oracle’s technology played a role in China’s Golden projects, a collection of early internet surveillance efforts. But after 2010, with Koh involved and Chinese surveillance projects going into overdrive, Oracle appears to have enthusiastically marketed its software for use by government entities, claiming it could be used for “centralized processing and smart analysis of public safety information.”

Some of the Chinese-language presentations on Oracle’s site are labeled “CONFIDENTIAL,” despite being publicly available. It is easy to see why someone might have wanted to keep them hidden. Taken together, they show an extreme willingness to aid in the construction of the surveillance state. One Chinese-language presentation, for example, promotes “Oracle’s recommendation: a more complete platform to meet the needs of public security big data processing.”

It is unknown exactly how many Chinese police departments may have used Oracle software for data analytics or predictive policing work beyond the departments — as implied in the documents — in Liaoning and Shanxi. Most of the Oracle China materials date to after the 2013 leak of documents by whistleblower Edward Snowden revealing that the National Security Agency had obtained access to the systems of U.S. technology companies. The Snowden revelations spooked Chinese government leaders and prompted renewed efforts to develop indigenous technologies, particularly for sensitive work involving police and the military.

But at the very least, the documents suggest that Oracle employees did detailed research on Chinese police and government operations, and crafted pitches based on that knowledge.

One notable Chinese-language presentation from 2014 describes a “Public Security Big Data Model,” depicted as a colorful bubble chart. At the center is a list of basic details that police might start with: a person’s name, national ID number, birth year, phone number, or QQ ID. (QQ is a popular instant messaging and social platform owned by the Chinese tech giant Tencent, which also owns the “super app” WeChat.) From there, the bubble chart links out to other data, including hotel check-ins; web and social media activity; and phone, bank, immigration, and vehicle records. Additional circles on the chart reference databases that Chinese authorities use to track drug users and people in the entertainment industry.

Sprick, the legal scholar, said that the entertainment industry databases are an ostensible public health measure meant to track at-risk people, including workers who engage in sex work, without criminalizing their activities. “If this data is now becoming directly accessibly by the police because some IT giant has a smart database architecture to offer, this public health issue can be hijacked by the public security organs and thereby endanger the aspired outcome of such a health tracking system,” he said. The chart suggests that Oracle pitched the ability to cross-reference basic identifiers with someone’s drug use or, indirectly, their sexual history.

Another pitch depicts a broad array of sensitive citizen data being converted into ones and zeros, including DNA, mental illness records, and other medical information. Still other documents from China boast that Oracle technology can help police trawl internet activity to “analyze potential suspected criminal behavior among hundreds of millions of netizens,” capture license plate data from “tens of thousands of cameras,” and analyze call records to build out criminal networks, then link them to fingerprint and facial recognition images.

Such emphases are consistent with previous findings about police surveillance in China. In 2017 and 2018, for example, Human Rights Watch published detailed reports on Police Cloud, the China-wide cloud computing project, and Integrated Joint Operations Platform, a predictive policing project in Xinjiang province. Both projects emphasize surveillance on specific categories of people named in the Oracle documents, including drug users and those with mental health problems.

The language in Oracle’s defense-focused presentations is also strikingly close to language that the Chinese military uses to characterizes its own agenda, according to Kania, the expert on Chinese defense strategy. One early military marketing presentation, from 2011, ticks off examples of Oracle’s work with the U.S. Defense Department before detailing how Oracle can help China with “military informatization,” a People’s Liberation Army buzzword. It reads, “We look forward to the opportunity to contribute to the transformation of cloud computing technology for the informatization of national defense.”

Selling to Xinjiang

Koh boasted on the LinkedIn account that he did so well at Oracle he was invited to an exclusive company gathering in Maui. But in 2016, he left for Chinese telecommunications equipment maker Huawei, where according to his bios he is the company’s global chief government industry scientist. He now hawks an analytics platform called FusionInsight. At Huawei, his work in Brazil continued. Huawei reportedly supplied João Doria, then mayor of São Paulo, with a gift of hundreds of surveillance cameras, and a news account indicated that Koh attended a meeting in China on the deal with Doria. Koh also was quoted speaking on behalf of Huawei after the company helped supply a controversial facial recognition system in Rio de Janeiro, saying the system could blend “facial recognition, behavior recognition and even objects.” The facial recognition system was used at Rio’s famed Carnival in 2019. In the first weeks of use, an innocent person was arrested.

Oracle’s efforts to work with police around the world continued after Koh’s departure. The Rio de Janeiro police still have active contracts with Oracle. The company also provides data centers and software to dozens of government agencies in Brazil, including universities, health agencies, ministries, and tribunals.

Do you have information about how Oracle products are used in China or in security applications? Have you worked with the company? Contact the author of this story, Mara Hvistendahl, on Signal at +1 651-400-7987 or at marahv@protonmail.com.

In China, meanwhile, an index of marketing seminars on Oracle’s site includes two apparent government-oriented cloud computing events from 2017. And a list of clients published on Oracle’s site last year said that the company provided “data security solutions” to the public security division in Xinjiang, along with five other Chinese provincial and city police departments, as well as the Ministry of Public Security itself. The document also lists telecommunications companies Huawei and ZTE as data security customers, both of which have come into the crosshairs of the U.S. government.

Moore, the Oracle spokesperson, said the company has “limited transactions with authorized ZTE and Huawei entities and NO transactions with any restricted ZTE or Huawei entities.” She conceded that Oracle had “limited authorized transactions with Xinjiang Public Security Bureau from 2011-2019,” adding that Oracle has not done business with the police bureau since the U.S. imposed sanctions on it in 2019.

“The entire system is run by the PSB. So if you are aiding them, you are aiding the camps.”

But for at least a year before Oracle says it ended its business with the police bureau, there was widespread global awareness of authorities in Xinjiang rounding up ethnic Uyghurs and other minorities and interning them in inhumane reeducation camps. The data collected by Xinjiang police included DNA samples, biometric information, and family planning histories, and it was shot through with ethnic, religious, and other forms of bias. “The Public Security Bureau is at the end of the chain of command,” said Darren Byler, an anthropologist who has written extensively about repression in Xinjiang. “The entire system is run by the PSB. So if you are aiding them, you are aiding the camps.”

Today Oracle continues to push into new markets, offering services that build foreign government demand for other Oracle products. Last October, Oracle launched a cloud hub in Dubai in collaboration with state-owned telecommunications company Etisalat, which helps implement internet censorship in the UAE.

Oracle chair Ellison reportedly told shareholders in the company’s December earnings call that the company’s work outside the United States is strategic and that its data centers and other services can lead to other business: “We’re just seeing demand for our products all over the world.” He added, “Our strategy is, because we have a large existing business, we have a large existing installed base, we believe we just have to get into more countries than someone — than Amazon.”

How Oracle Sells Repression in China (theintercept.com)

***

Share the link of this article with your facebook friends

|

|

|

|

||

|

||||||