www.aljazeerah.info

Opinion Editorials, July 2018

Archives

Mission & Name

Conflict Terminology

Editorials

Gaza Holocaust

Gulf War

Isdood

Islam

News

News Photos

Opinion Editorials

US Foreign Policy (Dr. El-Najjar's Articles)

www.aljazeerah.info

Reporting Hate Crimes: The Arab American Experience By James J Zogby Al-Jazeerah, CCUN, July 11, 2018 |

|

|

|

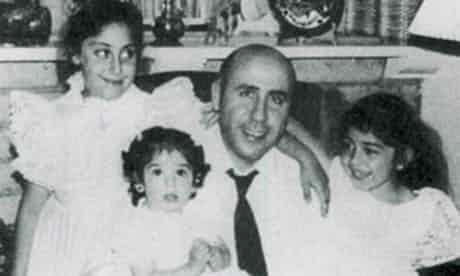

| Palestinian American Alex Odeh, who was assassinated by Zionists in 1985 |

Reporting Hate Crimes: The Arab American Experience

This week, the Arab American Institute Foundation will release a

comprehensive study on anti-Arab hate crimes in the US. The result of

eight months of work, "Underreported, Under Threat: Hate Crime in the

United States and the Targeting of Arab Americans," fills a gap in

available research on hate-based crime.

More than just a

compilation of acts of violence or threats against persons of Arab

descent, the AAIF study also reviews the history of how law enforcement

agencies have dealt with (or rather has not dealt with) anti-Arab hate

crimes. The report then rates the performance of all 50 states and the

District of Colombia as to whether or not they have hate crime and data

collection statutes, and require and provide appropriate law enforcement

training. It concludes with recommendations for national and local

governments to assist in improving their reporting and performance in

dealing with these crimes.

Among the report's findings we learn

that while pervasive negative stereotypes and political exclusion have

increased the vulnerability of Arab Americans, actual threats and

incidents of violence against members of the community have

"historically intensified in the wake of developments in the Middle East

or incidents of mass violence"—whether or not the perpetrator was of

Arab descent. The study notes with concern that this "backlash" effect

has "increased in the current political climate."

As the report

makes clear both federal and state governments have, to varying degrees,

been negligent in addressing this problem. The FBI started collecting

data on hate crimes, including those targeting Arab Americans, after

Congress passed the Hate Crime Statistics Act of 1990. But in 1992, the

federal government told the FBI it was not allowed to publish statistics

on anti-Arab hate crimes, and the category used to report anti-Arab hate

crimes was removed from the FBI’s data collections. This did not stop

local law enforcement agencies from reporting hundreds of incidents

under this category until 2003, when the FBI told agencies that it would

start rejecting “improperly coded data.” Even though the category was

reintroduced in 2015, the AAIF study shows that federal anti-Arab hate

crime statistics are still deficient. One indication is that state

governments report a greater number of anti-Arab hate crimes in their

own publications than federal statistics. In the case of nationwide data

targeting all communities, comparing hate crimes compiled by state

governments with federal data reveals "thousands of hate crimes were

reported at the state level but not published in federal statistics."

For me, this issue is deeply personal. I know from experience how

dangerous and painful anti-Arab hate can be. I received my first death

threat in April of 1970 in the form of a letter stating, "Arab dog, you

will die..." In 1980, my office was fire-bombed and I continued to

receive threats throughout the next two decades. After repeated threats,

a colleague and friend in California,

Alex Odeh, was murdered when his office was

bombed in 1985. And since September 11, 2001, three individuals have

gone to prison for threatening my life and the lives of my children and

staff.

In all of this, I have observed several patterns.

In most instances, these hate crimes were politically motivated and

were tied either to the perpetrator's racist assumption that all Arabs

were responsible for violent events in the Middle East or here at home.

Or they were an effort to silence me and other Arab Americans from

speaking out on issues of concern. While it is not the focus of the AAIF

report to discern the motives of the perpetrators of bias-motivated

incidents, my experience dictates the “why” is worth noting.

As I observed in Congressional testimony in 1985, in too many instances

the threats against us were preceded by incitement. As I noted,

"These acts of violence and threats of violence against Arab

American(s) are but part of a larger picture of discrimination,

harassment, and intimidation. We can document numerous instances of

active political discrimination against Arab Americans, 'blacklisting'

of Arab American political activists and spokespersons, and efforts to

bait or taint Arab American leaders and organizations as terrorists or

terrorist supporters.

All of these actions and practices

create a climate in which Arab Americans become fearful of speaking

freely and participating in legitimate political activity. Further,

these practices serve to embolden the political opponents of Arab

Americans to the point where, as we have seen, some have escalated their

opposition to include acts of violence against Arab Americans and their

organizations."

To the old adage "sticks and stones will break my

bones, but names will never hurt me", I have suggested adding "but

names, if repeated often enough, may incite others to commit violence."

It was no mere coincidence that some of the death threats against me and

my colleagues quoted material taken from virulently anti-Arab

publications or websites.

Another byproduct of persistent

defamatory attacks, some emanating from major pro-Israel organizations,

was to make it difficult for Arab Americans to normalize their political

involvement or to discourage others from becoming politically

engaged—which I believe was the purpose of the defamation. This, in

turn, historically played a role both in increasing the community's

vulnerability to threats and also in discouraging Arab American victims

from reporting them when threats occurred.

Why would discussions

of Middle East politics find their way to an analysis of hate crimes?

Because as the AAIF report notes, targeted violence against Arab

Americans is best contextualized within broader historical trends of

anti-Arab animus and the role exclusionary politics played in advancing

it. This exclusion, or the fear of being excluded, often made members of

the community reticent to go public when threatened.

Thankfully,

this situation has dramatically changed. While still subject to

defamation, Arab Americans are no longer excluded from the political

mainstream. Not only have we found our voice, but we have allies who

will come to our defense. And, despite real concerns with their work in

other areas, law enforcement agencies have become more responsive to

hate crimes against Arab Americans.

A final word about

the efforts of law enforcement in addressing hate crimes:

Over the

past four decades, the performance of federal law enforcement agencies

in addressing hate crimes has gone from deplorable to commendable. Early

on, Arab Americans even hesitated to report death threats because of the

behavior of the agents who came to visit us. After the 1980 fire bombing

for example, I ended up feeling that I was being grilled more for

information about the Arab community, then about the likely

perpetrators—members of an FBI designated terrorist group, the Jewish

Defense League (JDL). The JDL had issued a statement "approving" of the

attack and the group's founder later appeared outside my new office

shouting,

"I know who is in there—cowards and supporters of

terrorism. Their office was burned down. They ran over here and changed

their name. But we know who they are."

In 1985, I went to the

Director of the FBI with over 100 affidavits from Arab Americans in the

Los Angeles area complaining of FBI harassment and a dozen reporting

threats of violence. I pointedly asked, "why do you spend so much time

and resources harassing us and so little time defending us." A few

months later, one of the Arab Americans who had reported a threat, Alex

Odeh, was murdered in a bombing attack on his office.

Since 9/11,

the situation changed quite dramatically. The FBI and the Department of

Justice Civil Rights Division have taken threats seriously. While other

problems remain, in this area they have been quite protective of the

community - investigating, prosecuting, and convicting individuals in

over one hundred hate crime cases.

It is this context of the progress made and the work that remains to be done that the AAIF report has been issued. It will, I believe, serve as an invaluable resource for policy makers, law enforcement agencies, and community groups.

***

Share the link of this article with your facebook friends

|

|

|

|

||

|

||||||