Al-Jazeerah History

Archives

Mission & Name

Conflict Terminology

Editorials

Gaza Holocaust

Gulf War

Isdood

Islam

News

News Photos

Opinion

Editorials

US Foreign Policy (Dr. El-Najjar's Articles)

www.aljazeerah.info

|

|

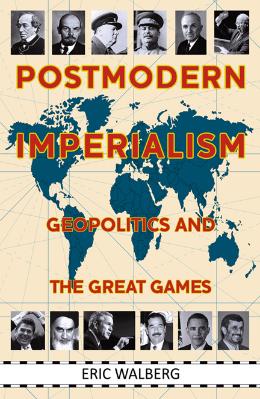

Postmodern Imperialism: Geopolitics and the Great

Games

a Book By Eric

Walberg

Clarity Press, 2011

Al-Jazeerah, CCUN, May 18, 2015

http://www.claritypress.com/Walberg.html

|

"Walberg’s

volume is a bold attempt to make sense of the contemporary world

we live

in. His analyses and interpretations

provide another and more critical way of seeing the events that

have occurred over the century. For those who are searching for

a critical perspective and stance towards US foreign policy and

the role of Israel in global affairs, then

Postmodern

Imperialism

is an ideal

selection."

European

Journal of American Studies

“Walberg’s

book is a sharp and concise energizer package required to

understand what

may follow ahead of the Great 2011

Arab Revolt and related geopolitical earthquakes.

It’s a carefully argued—and most of all, cliche-smashing—road

map showing how the

New Great Game in Eurasia is in

fact part of a continuum since the mid-19th century.

Particularly refreshing is how Walberg characterizes Great Games

I, II and III—their

strategies and their profiteers.

Walberg also deconstructs an absolute taboo—at least in

the West: how the US/Israeli embrace has been a key

feature of the modern game. It

will be hard to

understand the complex machinery of post-imperialism without

navigating this ideology-smashing road map.”

PEPE

ESCOBAR, roving correspondent for

Asia Times,

author

of

Globalistan: How the Globalized World is

Dissolving

into Liquid War

(2007)

"The author

has succeeded in describing the conditions and objectives of the

post-

modern imperialism and to clarify it as a

continuation of classical imperialism; the book

contains a wealth of information, and will be an important

reference for understanding

the historical and

current events, and expectations for the future."

ZIAD

MUNA,

AL JAZEERA

"as much of

a sober analytical study of European history as any issuing from

the

worldview of Eurocentric modernism..."

Muslim

World Book News

“Those who

think that the “Great Game” played for control of Central Asia

is a

superannuated relic of Europe’s imperial past

must read Walberg’s epic corrective to

their

egregious error. In extensive, richly textured and carefully

documented detail he

reveals the evolution of this

competition into the planetary quest for dominance it has

become, as well as the imperatives animating its new

“players,” among whom many will

find, to their

surprise or consternation, tiny Israel and its symbiotic liaison

with America

Inc. Prime imperial architect, Zbigniew

Brzezinski actually called the blood-soaked

playing

field The Grand Chessboard, but like all his rapacious forebears

omitted to

mention the pawns. Walberg places them at

the heart of this much needed remediation

of the

sinister falsehoods propagated in a political culture

manufactured from above

and offers hope that this

anti-human playboard may yet be overturned."

PAUL

ATWOOD, American Studies, University of Massachusetts

and

author of War and Empire: The American Way of Life (2010)

"Imperialism is as alive today as in the days of the original

Great Game. Central

Asia and the Middle East are as

strategically important today for the US and Great

Britain as they were in earlier games, if for different reasons.

Postmodern

Imperialism

is a continuation of Kwame Nkrumah’s

Neocolonialism: The Last Stage

of Imperialism

(1965) and carries forward the struggle of the pen against the

sword."

GAMAL

NKHRUMAH, international editor, Al-Ahram Weekly, Cairo

"Walberg’s

provocative work traces the transformation of the imperial world

through the twentieth century. It is a valuable

resource for all those interested in

how imperialism

works, and is sure to spark discussion about the theory of

imperialism and the dialectic of history."

JOHN

BELL, author of Capitalism and the Dialectic (2009)

"In his

brilliant and newly released book, “Postmodern Imperialism:

Geopolitics and

the Great Game”, Eric Walberg

astutely charts NATO’s role following the end of the

Cold War. NATO “has become the centerpiece of the (US) empire’s

military presence

around the world, moving quickly

to respond to US needs to intervene where the UN

won’t as in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq and now Libya.”"

RAMZY

BAROUD,

Al-Arabiya

"Walberg's

"Postmodern Imperialism" is a landmark text, written at a

crucial

moment in time. For the West, America and

Americans, this may be a final wake-up

call."

GILAD

ALTZMON,

Counterpunch

“the best

introduction to geopolitics that I have seen”

KEVIN

BARRETT,

Veterans

Today

“Eric

Walberg’s treatise on the Great Games, on Empire, is an

excellent read. It is

not a blow by blow account of

the rise and fall of empires involved with the Great

Games, but an accounting of their methods and raison d’etre. It

is a dense read,

provocative, bold, touching on

ideas that seldom appear in mainstream

presentations. It is a significant and important addition to

the geopolitical and

political-military thinking of

the global cultural environment of finance and wars.”

JIM

MILES,

Foreign

Policy Journal

and

Palestine

Chronicle

The

term “Great Game” was coined in the nineteenth century to

describe

the rivalry between Russia and Britain.

The ill-fated Anglo-Afghan war of

1839–42 was

precipitated by fears that the Russians were encroaching on

British interests in India after Russia

established a diplomatic and trade

presence in

Afghanistan. Already by the nineteenth century there was no

such thing as neutral territory. The entire

world was now a gigantic playing

field for the

major industrial powers, and Eurasia was the center of this

playing field.

The game motif is useful

as a metaphor for the broader rivalry between

nations and economic systems with the rise of imperialism

and the pursuit

of world power. This game has

gone through two major transformations

since the

days of Russian-British rivalry, with the rise first of

Communism

and then of Islam as world forces

opposing imperialism.

The main themes of Postmodern

Imperialism: Geopolitics and the Great

Games

include:

-

US

imperial strategy as an outgrowth of British imperialism,

and its

transformation following the collapse of

the Soviet Union;

-

the

significance of the creation of Israel with respect to the

imperial

project;

-

the

repositioning of Russia in world politics after the collapse

of the

Soviet Union;

-

the

emerging role of China and Iran in Eurasia;

-

the

emerging opposition to the US and NATO.

As the

critical literature on NATO, the new Russia, and the Middle

East is

fragmented, this work brings these

elements together in historical

perspective with

an understanding from the Arab/ Muslim world’s point of

view, as it is the main focus of all the “Great

Games”. It strives to bridge the

gap between

Western, Russian and Middle Eastern readers with an

analysis that is accessible and appeals to all

critical thinkers, and at the

same time provides

the tools to analyze the current game as it evolves.

The Great Games of yore – Britain vs. Russia and their

empires in the 19th

century, and the US vs. the

Soviet Union in the 20th century – no longer

translate merely as the US vs. Russia or Russia/ China. A

major new

player is a collective one, NATO,

which today is as vital as the emperor’s

clothes

to justify the global reach of US imperialism. Today, the

“playing

field” – the geopolitical context – is

broader than it was in either the 19th or

20th

century games, though Eurasia continues to be “center

field”, where

most of the world’s population and

energy resources lie.

The

existence of Israel is an anomaly which seriously

complicates the

shaping of the geopolitical

game. Its roles in the Great Games as both

colony and an imperial power in its own right, is analyzed

in the context of

the history of Judaism and its

relations with both the western Christian and

the Muslim worlds.

PREFACE

To young people today, the world as a global village appears

as a given, a ready-made order, as if human

evolution all

along was logically moving towards our high-tech, market-driven

society, dominated by the

wealthy United States. To bring

the world to order, the US must bear the burden of oversize

defense

spending, capture terrorists, eliminate dictators,

and warn ungrateful nations like China and Russia to

adjust

their policies so as not to hinder the US in its altruistic

mission civilatrice.

The reality is something else entirely,

the only truth in the above characterization being the

overwhelming military dominance of the US in the world today.

The US itself is the source of much of the

world’s

terrorism, its 1.6 million troops in over a thousand bases

around the world the most egregious

terrorists, leaving the

Osama bin Ladens in the shade, and other lesser critics of US

policies worried about

their job prospects.

My own

realization of the true nature of the world order began with my

journey to England to study

economics at Cambridge

University in September 1973. I decided to take the luxury SS

France ocean

liner which offered a student rate of a few

hundred dollars (and unlimited luggage), where I met American

students on Marshall and Rhodes scholarships (I had the less

prestigious Mackenzie King scholarship), and

used my wiles

to enjoy the perks of first class. The ship was a microcosm of

society, a benign one. The

world was my oyster and I wanted

to share my joy with everyone.

But I was in for a shock.

Cambridge was also a microcosm of society, but a very different

one. My friends

at Cambridge included many Latin Americans,

and the tragic events of that September 11 – the US-

orchestrated coup against Salvador Allende in Chile – were what

I was to cut my political teeth on. The

look of despair on

the face of a Chilean friend, suddenly a refugee whose friends

and family were now in

peril, was etched in my memory. That

began my path of study and activism, and drove home to me the

essence of the world political and economic system.

Imperialism was not an abstraction, but a

devastating force

that destroyed good, idealistic people, whole peoples. Enemies

of imperialism must be

reconsidered, in the first place, the

Soviet Union, which until then I had accepted as a dangerous and

evil force in the world.

I immediately began

studying Russian and was determined to experience Soviet reality

from the inside.

The “Soviet threat” was the pretext for

Nixon’s undermining the Chilean revolution. It was the pretext

for

the blockade of Cuba. It was the pretext for the horrors

the US was inflicting on the Vietnamese. Was it

really the

evil empire which I had been indoctrinated into fearing and

loathing my entire life? I had to

find out for myself.

Looking back on this turning point in my life, I can only

marvel at the few slight breathing spaces in the

Cold War

that allowed people to reject the capitalist paradigm, to

realize who the real enemy is. As

opposed to Thatcher's TINA

(There Is No Alternative) – There Was An Alternative (TWAA)!

Fear of this

‘enemy’ quickly evaporated among intelligent

mainstream people in the West during the periods of

detente

(1941–48, 1963–68, 1973–79). These brief respites were tactical

retreats in the long-term fight by

imperialism, biding its

time.

My studies were framed by the coup in Chile

in September 1973 and the liberation of Saigon in the

spring

of 1975. Celebrating the latter moment with my friends in the

university cafeteria is also etched in

my mind. The world

belonged to us. The low point for US imperialism, the high point

(the last, it turned

out) for the Soviet Union. I studied

with Marxists such as Maurice Dobb, and neo-Ricardians such as

Piero

Sraffa, Luigi Pasinetti, and Joan Robinson, and

suddenly saw the twentieth century through new lenses.

Upon my return to Toronto, I sought out what I learned were

called “fellow travelers”. There weren't so

many as I

expected. In desperation, I looked in the phone book under USSR,

but there was not even a

Soviet Consulate in Canada’s

largest city (though there was a Bulgarian, a Czech, even a

Cuban one). I

eventually stumbled across the Canada-USSR

Friendship Society, a motley collection of primarily Slavic

and east European immigrants, Jews, with a smattering of WASP

peaceniks. A friendly if doctrinaire

group, with no sign of

any super spies like Kim Philby. In retrospect, I see that the

peacenik contingent

was more conspicuous in its absence.

With great difficulty, I got to Moscow in 1979 to

study Russian at Moscow State University (MGU) through

the

Friendship Society, a bizarre and memorable experience to say

the least. I fell sick and became sicker

after a short stay

in a filthy hospital, but managed to stick it out till we were

peremptorily shunted to

unfinished Olympic accommodations in

order to make room for newly revolutionary Ethiopian students at

MGU.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan took place as

we trudged through the freezing mud to our new

residence in

December, the subsequent collapse of détente playing out on an

international stage my own

frustrations with “real existing

socialism”, a system that left no room for criticism or doubt in

the face of

much nonsense and cruelty.

My former

enthusiasm for Soviet-style communism* was gone; however, on

returning to North America, I

was faced with the mindless

propaganda and belligerence of Reagan America, and I realized

that my

love affair with the ornery Soviet beast was not

over – TWAA. When Gorbachev dismantled censorship

(glasnost)

and began his ill-fated economic reforms (perestroika), I landed

a job at Moscow News. My

sense of urgency in getting there

ASAP was not ill-founded, as it turned out.

The

brief respites from the Cold War and this final crazy attempt to

create a ‘nice’ socialism were indeed

remarkable. The US

actually feared and respected another country, and that country

held out its

diplomatic hand in friendship, only to find

itself subverted by its new ‘friend’. The Bushes and now Obama

have all vowed since never to let another country challenge

the US militarily again. How ironic, now that

military

superiority has lost all meaning in an age of dirty bombs and

anthrax.

The Soviet Union produced environmental

disasters, notably the death of the Aral Sea. Collective

farming enforced at gunpoint destroyed a vibrant peasant

tradition. The gulags and Stalinist repression

were a

terrible tragedy. But colonialism and fascism killed far more

innocent people, and both were

aggressive, starting wars

with other countries. The Soviet Union was a one-party system, a

dictatorship, but

not an aggressively expanding empire,

contrary to what we were and are indoctrinated into believing.

For all its political flaws, it showed the viability

of a non-capitalist way of organizing technologically

advanced urban society. Its economic flaws – inefficiency,

sloppiness, low standards, ecological

disregard – were

countered by its pluses – guaranteed employment, free public

services, encouragement

of modest material needs, broad

access to culture, security for the individual, a less

competitive more

egalitarian lifestyle. This is how it was

understood in the third world, where its passing is still

mourned.

Until the collapse of the Soviet Union,

the main foe of Israel, I hadn’t paid special attention to the

Middle

East, assuming that as the anti-imperialist forces

grew, Israel would be pressured to make peace. The

assassination of Yitzak Rabin in 1994 and the ascendancy of the

neocons made it clear that this was not

going to happen.

The defeat of communism meant that the only remaining

anti-imperialist cultural force was Islam, and I

was drawn

to Uzbekistan in Central Asia, with a vibrant Muslim heritage.

This culminated in another major

turning point for me –

watching the twin towers collapse 28 years after the “9/11” coup

in Chile, on that

more familiar “9/11” of 2001, in bleak

post-Soviet Tashkent.

My immediate reaction was

that their collapse simply could not be the work of a band of

poorly trained

Muslims orchestrated by someone in a cave in

neighboring Afghanistan. Subsequent study has confirmed

to

me that the events of 2001 had far more to do with US

imperialism – and Israel – than Islam.

I am

fortunate to have lived my life on both sides of the “Iron

Curtain” and now in the heart of the

supposed enemy today –

the Islamic world. This has given me the opportunity to

experience alternative

realities, to step back from my

western heritage and see more clearly how the western world

confronts and

plays with other countries and cultures. There

are many such journeys of discovering by people coming of

age politically. I hope my reflections provide readers the

opportunity to step back from their frame of

reference, and

help them understand the games we are forced to play.

***

*A note on the use of the term communism, capitalism and

imperialism: communism refers to both the

theory as proposed

by Marx and the attempts to realize the theory as embodied in

the social formations of

post-1917 Russia and post-WWII

eastern Europe. While the latter strayed far from the theory,

they were

nonetheless inspired by Marx. Critics may replace

“communism” with “failed workers’ state” or “state

capitalism” as they like. This does not undermine the overall

thesis about communism made here. I treat

the terms

capitalism and imperialism as scientific terms as used by Marx

and Lenin. The Soviet Union

became a ruthless dictatorship

under Stalin, but the logic of it and its relations with eastern

Europe was

not imperialist. To use such terms cavalierly to

refer to noncapitalist social formations would reduce any

analysis to rubble -- a kind of intellectual 9/11, an apt

metaphor for how US capitalist mind-control

prevents any

real opposition from taking root.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1 The Great Games: Imperialism in

Central Asia and the Middle East

Geopolitics of Central Asia

and the Middle East

The games as variants of imperialism

Goals

Strategies

Chapter 2 GGI: Competing

empires

Beginnings of GGI and goals

Ideology

Rules of

the game and Strategies

Finance Strategies

Military-political Strategies

Institutions

Hard power

Soft power

Control of world resources

Endgame 1914–45

Chapter 3 GGII: Empire against Communism

Beginnings of

GGII and goals

Ideology

Rules of the game and Strategies

Finance Strategies

Military-political Strategies

Decolonization, institutions (UN, EU, NATO, pactomania, CFR,

Bilderberg,

Trilateral Commission),

Hard power (war,

black ops, arms race, MAD),

Soft power (aid, culture,

Islamists, drugs)

Control of world resources

Endgame

1979–91

Appendix: GGII imperial doctrines

Chapter 4

GGIII: US-Israel – Postmodern imperialism

The struggle to

establish the new GGIII goals

Ideology

Rules of the game

and Strategies

Financial Strategies

Military-political

Strategies

GGIII Imperial Doctrines, institutions (UN,

NATO, pre/ postmodern

states)

Hard power (wars, military

bases, missile defense, cyber warfare,

arms production,

nuclear weapons, proxies)

Soft power (aid, NGOs, colour

revolutions, co-opting regimes, anti-

piracy, drugs, domestic

repression)

Control of world resources

Appendix:

Critique of ‘New NATO’ literature

Chapter 5 GGIII: Israel

– empire-and-a-half

Judaism and Zionism

Jews and the

state through history

GGI

GGII&III

Ideology – from

diaspora ghetto mentality to nationalism, liberalism, communism

and

neoconservatism

Rules of the game and Strategies –

GGII&III

Financial Strategies – Money and Finance – GGI,

Mafia – GGIII

GGIII Military-political Strategies

GGIII doctrines,

Hard power (wars, arms production, nuclear

weapons, terrorism/

mercenaries/ mafia)

Soft power (politicide

and co-opting the PLO, use of Islamists, spies/ assets/

sayanim/ gatekeepers, Israel lobby, media manipulation, culture

wars)

Penetrating US imperial strategic thinking

Control of world resources

Endgame

Appendix I: The Israel

lobby and ‘Dog wags the tail’ debate

Chapter 6 GGIII:

Many players, many games

Major players

Conclusion

Appendix I: Critique of ‘New Great Game’ literature

Appendix

II: GGIII Alliances

Appendix III: The ex-Soviet Central Asian

republics in GGIII

|

|

***

Share this article with your facebook friends

|

|

|