www.aljazeerah.info

News, December 2021

Archives

Mission & Name

Conflict Terminology

Editorials

Gaza Holocaust

Gulf War

Isdood

Islam

News

News Photos

Opinion Editorials

US Foreign Policy (Dr. El-Najjar's Articles)

www.aljazeerah.info

|

Editorial Note: The following news reports are summaries from original sources. They may also include corrections of Arabic names and political terminology. Comments are in parentheses. |

Heroes of 2021

Researchers Who Contributed to

Finding Covid-19 Vaccines,

and All Health Workers Who Treated the Pandemic Patients Around the World

December 21, 2021

The heroes of 2021 have been the researchers, who contributed to finding Covid-19 vaccines, together with all health care workers who treated the pandemic patients around the world.

Here are examples of researchers who were involved in finding the Covid-19 vaccines in the US, UK, Germany, Russia, China, and India. There are thousands of other researchers who worked with them in these countries and around the world. Likewise, there have been millions of heroes in the health care services in all countries of the world, who worked hard to treat patients of the pandemic, since its break.

To all of them: Thank you for your great efforts in the service of humanity.

|

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett | Dr. Hana El Sahly | Dr. Ugur Sahin, left, and Dr. Ozlem Tureci | Dr. Alexander Gintsburg | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Chen Wei | Dr. Zhang Yongzhen.jpg |

Dr. Sarah Gilbert and Dr. Andrew Pollard |

Dr. Shahid Jameel |

Dr. Hana El Sahly

Dr. Hana El Sahly is a professor of molecular virology and microbiology and of medicine – infectious diseases. Since 2016, Dr. Hana El Sahly has served as principal investigator at Baylor’s National Institutes of Health-funded Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit, where she and her team conduct translational research of vaccine candidates, including vaccines for influenza, neglected tropical diseases and agents that could be used as bioweapons. She is an international leader in translational research of vaccines and her leadership and scientific rigor have been recognized with appointments to World Health Organization, the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration and the Wellcome Trust scientific advisory panels and boards.

As the leader of Baylor’s Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit, El Sahly played a critical role in the response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, serving as the co-principal investigator and co-first author of the study that established the clinical efficacy of the Moderna mRNA vaccine in preventing COVID-19. El Sahly was selected as one of three national co-principal investigators of the phase 2 study of the Moderna vaccine and, in this role, made significant contributions to the study design and development of standardized outcomes.

In addition, she and colleagues at Baylor initiated the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial, which proved the clinical efficacy of remdesivir in treating SARS-CoV-2. Remdesivir remains the only antiviral medication approved for treating SARS-CoV-2. El Sahly and colleagues also found that the use of remdesivir plus baricitinib, a targeted anti-inflammatory, improved outcomes in COVID-19 patients, especially those requiring oxygen.

In addition to her work during the pandemic, El Sahly has led clinical trials on influenza pandemic preparedness, the universal influenza vaccine, Zika virus infection, chikungunya and schistosomiasis.

Baylor College of Medicine celebrates research excellence with DeBakey Awards (bcm.edu)

***

Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett

Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett was ready, willing, and able when the COVID-19 pandemic emerged to take the critical first steps in developing what would become the Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccines.

More than 170 million Americans already have received COVID-19 vaccines. As this number continues to grow and expand to younger age groups, I’m filled with overwhelming gratitude for all of the researchers who worked so diligently, over the course of decades, to build the scientific foundation for these life-saving vaccines. One of them is Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, who played a central role in the fact that, in the span of less than a year, we were able to develop safe and effective mRNA-based vaccines to protect against this devastating infectious disease.

As leader of the immunopathogenesis team at NIH’s Dale and Betty Bumpers Vaccine Research Center in Bethesda, MD, Dr. Corbett was ready, willing, and able when the COVID-19 pandemic emerged to take the critical first steps in developing what would become the Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccines. Recently, she accepted a position at Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, where she will soon open her own viral immunology lab to help inform future vaccine development for coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses.

While she was preparing for her move to Harvard, I had a chance to speak with Dr. Corbett about her COVID-19 research experience and what it was like to get immunized with the vaccine that she helped to create. Our conversation was part of an NIH Facebook Live event in which we connected virtually from our homes in Maryland. Here is a condensed version of our chat.

Meet an Inspiring Researcher Who Helped Create COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines – NIH Director's Blog

***

Dr. Sarah Gilbert and Dr. Andrew Pollard

Life savers: the amazing story of the Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid vaccine

Exactly a year ago (February 2020), Oxford University scientists launched a joint enterprise that is set to have a profound impact on the health of our planet. On 11 February, research teams led by Professor Andy Pollard and Professor Sarah Gilbert – both based at the Oxford Vaccine Centre – decided to combine their talents to develop and manufacture a vaccine that could protect people from the deadly new coronavirus that was beginning to spread across the world.

A year later that vaccine is being administered to millions across Britain and other nations and was last week given resounding backing by the World Health Organization. The head of the WHO’s department of immunisation, vaccines and biologicals, Professor Kate O’Brien, described the jab as “efficacious” and “an important vaccine for the world”.

It has been a remarkable journey for the Oxford Vaccine Group and in particular for its leaders, Gilbert and Pollard, who have worked tirelessly to create their cheap, easy-to-distribute vaccine and to defend it, patiently and politely, from attacks by pundits and politicians.

In developing a Covid vaccine that is easy to transport and cheap to administer, the Oxford Group has again underlined the strength of UK science, which has already been bolstered by the country’s remarkable Recovery trial which last week revealed the efficacy of another lifesaving, anti-Covid drug: Tocilizumab.

In addition, Britain’s geneticists have been hailed for their efforts in detecting potentially dangerous new virus strains – by carrying out the lion’s share of virus variant sequencing across the planet.

Then, at the end of 2019, a novel, occasionally fatal respiratory illness appeared in Wuhan, the sprawling capital of central China’s Hubei province, and by early January was spreading outside China.

The Shanghai virologist Professor Zhang Yongzhen first decoded the virus’s genetic structure and published his results on the internet. Gilbert and her colleagues immediately began working on a vaccine using Zhang’s data.

However, it quickly become clear that the new outbreak was going to be something very much bigger than early cases had suggested and much larger trials of vaccines would be needed. So Gilbert sought the advice of Pollard, a paediatrician and expert on running large-scale vaccine trials. “Normally we work on our own projects,” said Pollard. “But we quickly realised this was something that needed a large team to tackle. So we brought our research groups together.”

To create their vaccine, the Oxford team took a common cold virus that infects chimpanzees and engineered it so that it would not trigger infection in people. Then they further remodified it so that it carried the genetic blueprints for pieces of coronavirus. These would be carried into cells in the body, which would then start to make pieces of coronavirus to train people’s immune system to attack them. Armed with this technology, the Oxford scientists – later backed by the pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca – were then able to manufacture their vaccine and begin testing.

Life savers: the amazing story of the Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid vaccine | Coronavirus | The Guardian

Professor Gilbert holds the Saïd Professorship of Vaccinology. She joined the Nuffield Department of Medicine at Oxford University in 1994 and became part of the Jenner Institute (within NDM) when it was founded in 2005. Her chief research interest is the development of viral vectored vaccines that work by inducing strong and protective T and B cell responses.

She leads the Jenner Institute programme in influenza vaccine development and now also works on vaccines for many different emerging pathogens, including Nipah, MERS, Lassa and CCHF. Working with colleagues in the Jenner Institute research labs, the Clinical Biomanufacturing Facility and Centre for Clinical Vaccinology and Tropical Medicine, all situated on the Old Road Campus in Oxford, she is able to take novel vaccines from design to clinical development, with a particular interest in the rapid transfer of vaccines into GMP manufacturing and first in human trials. She is the Oxford Project Leader for ChAdOx1 nCoV-19.

The University of Oxford, in collaboration with AstraZeneca plc, announces interim trial data from its Phase III trials that show its candidate vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV-2019, is effective at preventing COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) and offers a high level of protection.

The Oxford Vaccine | Research | University of Oxford

***

Dr. Ugur Sahin and Dr. Ozlem Tureci

Two years ago, Dr. Ugur Sahin took the stage at a conference in Berlin and made a bold prediction. Speaking to a roomful of infectious disease experts, he said his company might be able to use its so-called messenger RNA technology to rapidly develop a vaccine in the event of a global pandemic.

At the time, Dr. Sahin and his company, BioNTech, were little known outside the small world of European biotechnology start-ups. BioNTech, which Dr. Sahin founded with his wife, Dr. Özlem Türeci, was mostly focused on cancer treatments. It had never brought a product to market. Covid-19 did not yet exist.

But his words proved prophetic.

On Monday, BioNTech and Pfizer announced that a vaccine for the coronavirus developed by Dr. Sahin and his team was more than 90 percent effective in preventing the disease among trial volunteers who had no evidence of having previously been infected. The stunning results vaulted BioNTech and Pfizer to the front of the race to find a cure for a disease that has killed more than 1.2 million people worldwide.

After BioNTech had identified several promising vaccine candidates, Dr. Sahin concluded that the company would need help to rapidly test them, win approval from regulators and bring the best candidate to market. BioNTech and Pfizer had been working together on a flu vaccine since 2018, and in March, they agreed to collaborate on a coronavirus vaccine.

Since then, Dr. Sahin, who is Turkish, has developed a friendship with Albert Bourla, the Greek chief executive of Pfizer. The pair said in recent interviews that they had bonded over their shared backgrounds as scientists and immigrants.

“We realized that he is from Greece, and that I’m from Turkey,” Dr. Sahin said, without mentioning their native countries’ long-running antagonism. “It was very personal from the very beginning.”

Early in his career, he met Dr. Türeci. She had early hopes to become a nun and ultimately wound up studying medicine. Dr. Türeci, now 53 and the chief medical officer of BioNTech, was born in Germany, the daughter of a Turkish physician who immigrated from Istanbul. On the day they were married, Dr. Sahin and Dr. Türeci returned to the lab after the ceremony.

In 2001, Dr. Sahin and Dr. Türeci founded Ganymed Pharmaceuticals, which developed drugs to treat cancer using monoclonal antibodies. Dr. Sahin and Dr. Türeci sold Ganymed for $1.4 billion in 2016. Last year, BioNTech sold shares to the public; in recent months, its market value has soared past $21 billion, making the couple among the richest in Germany.

***

Dr. Alexander Gintsburg

Alexander Gintsburg, head of the Gamaleya Institute that produced the Sputnik V vaccine.

The world is on the brink of a third coronavirus wave, Western governments are imposing lockdowns, one after another, and a vaccine war is raging worldwide. No one can tell for sure when the madness will be over. Gamaleya Center Director Alexander Gintsburg talks with Interfax correspondents Andrei Novikov and Olga Gavrilyuk about the prospects for the fight against Covid-19, its new strains, and work on a new universal vaccine.

Question: If we may, let's start at the end, with the recent news that the Argentinean president got sick. In your opinion, has this incident dealt a blow to the reputation of the Sputnik V vaccine? Has it threatened its advancement?

Answer: I don't think so, because there was no actual disease. There was the infection, there was isolation, but he had no treatment and no symptoms during this infection. So this does not just fit into the vaccine's mechanism of action, but at the same time it also underlines the medicine's reliability, proves one of the main conclusions made in the Lancet publication – Sputnik V gives a 100% guarantee against serious diseases that require hospitalization. The Argentinean president is smart man, he made a public statement saying that he was very thankful to Russia and that he understood that had he not been vaccinated, the disease would have likely become grave.

Sputnik V booster strengthens Omicron defence, developer says

A booster shot of Russia's Sputnik Light vaccine provides a stronger antibody response against the Omicron variant of COVID-19 than the two-dose Sputnik V vaccine alone, the medicine's developer said on Friday.

Moscow's Gamaleya Institute said a preliminary study showed a Sputnik Light booster applied six months after a second Sputnik dose gave better protection against Omicron, which is driving a wave of infections in Europe.

"All the serum samples from (revaccinated) people that were tested contained the required level of virus-neutralizing antibodies in relation to the Omicron variant," said Alexander Gintsburg, head of the Gamaleya Institute.

Gintsburg did not say how many people took part in the study, which compared the antibody response in people at different stages of vaccination.

The Russian Direct Investment Fund, which markets Sputnik V internationally, said in a statement two shots of Sputnik V also provided a strong defence against serious symptoms and hospitalisations caused by Omicron, contradicting an international study that found Sputnik did not offer protection against the new variant.

The efficacy of Sputnik V in combination with its booster could stand at 83% or higher, the same as it showed against the Delta variant, Gintsburg said. He said the institute would publish its findings in a peer review publication.

Sputnik V booster strengthens Omicron defence, developer says | Reuters

***

Dr. Chen Wei

In February 2020, China got off to the races in developing a viable COVID-19 vaccine when Chen Wei, epidemiologist and major general in the People’s Liberation Army, appeared on state-run television and injected herself with a COVID-19 vaccine the military developed in partnership with private maker Cansino that had yet to be tested on animals, let alone humans.

The move was an early indication that China’s approach to developing and distributing COVID vaccines would divert from the regimented clinical trial processes that places like the U.S. and Europe adhered to.

In July, China launched its emergency use program, distributing doses from Sinovac, Sinopharm, and private Beijing firm Cansino to the Chinese population before the companies had completed Phase III trials to test how well the vaccines protected against the virus. By November 2020, Sinopharm alone reported that it had distributed over 1 million COVID-19 jabs to the public.

China’s risky COVID-19 vaccine development strategy paid off | Fortune

Chen Wei: She-power behind China's first COVID-19 vaccine By Pan Zhaoyi

When a patriotic action movie named "Wolf Warrior II" broke China's box-office records in 2017, a less-prominent figure unexpectedly left a strong impression on the audience – a military scientist that developed a vaccine for a deadly virus spreading across Africa.

A year later, a real military scientist Dr. Chen Wei, 54, was sent from China to Sierra Leone to help the African country fight against the deadly Ebola, and with a real vaccine.

The only difference between the two figures is that the real Dr. Chen is "she."

A mother, daughter and wife, Dr. Chen is a female general in the Chinese People's Liberation Army. She came back in the spotlight after she led the team developing China's first COVID-19 vaccine.

Data shows hashtags and posts related to #China's first coronavirus vaccine approved for clinical trials# have received over 520 million views and more than 127,000 comments on the country's Twitter-like social media platform Weibo.

Dr. Chen was recalled to Wuhan, the epicenter of the virus one day after the Chinese Lunar New Year, China's biggest holiday family reunion. She and her team didn't waste a minute to work in a makeshift lab for research and testing. And almost 50 days later, the first vaccine was ready for clinical trials.

Chen Wei: She-power behind China's first COVID-19 vaccine - CGTN

China’s COVID vaccines have been crucial — now immunity is waning

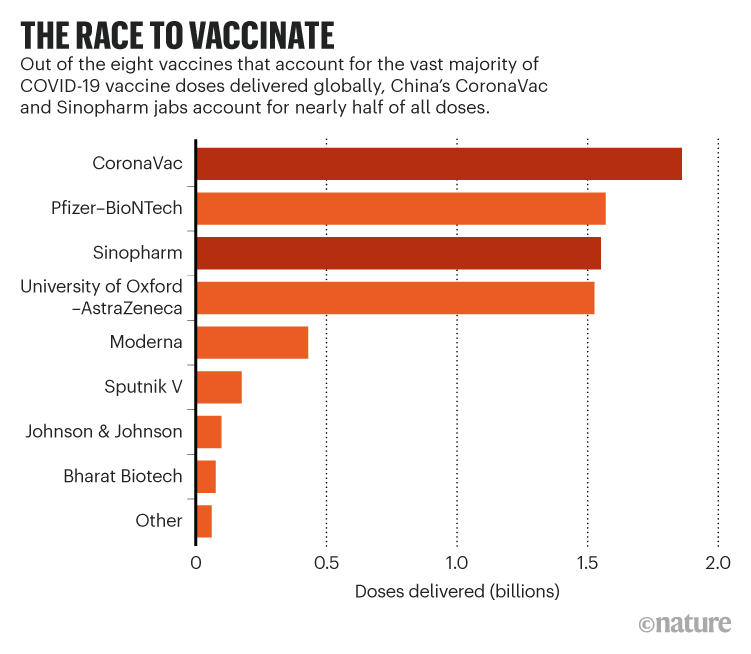

Billions of shots of China’s CoronaVac and Sinopharm vaccines have been given globally, but studies have questioned the length of protection they offer.

China’s CoronaVac and Sinopharm vaccines account for almost half of the 7.3 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses delivered globally, and have been enormously important in fighting the pandemic, particularly in less wealthy nations.

But as the doses mount, so have the data, with studies suggesting that the immunity from two doses of either vaccine wanes rapidly, and the protection offered to older people is limited. This week the World Health Organization announced advice from its Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) that people over 60 should receive a third dose of the same or another vaccine to ensure sufficient protection.

China’s COVID vaccines are going global — but questions remain

The recommendation is “sensible and necessary”, says Manoel Barral-Netto, an immunologist at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Salvador, Brazil.

A number of countries are already offering third doses to all adults or are trying mix-and-match approaches. Some experts are even questioning whether China’s jabs — based on inactivated virus — should continue to be used at all when other options are available.

China’s COVID vaccines have been crucial — now immunity is waning (nature.com)

***

Dr Zhang Yongzhen

The Chinese Scientist Who Sequenced the First COVID-19 Genome Speaks Out About the Controversies Surrounding His Work

Zhang believes science holds the key to predicting viral outbreaks with similar accuracy as with which we now anticipate typhoons and tornadoes. “If we don’t learn lessons from this disease,” says Zhang, “humankind will suffer another.”

Over the past few years, Professor Zhang Yongzhen has made it his business to sequence thousands of previously unknown viruses. But he knew straight away that this one was particularly nasty. It was about 1:30 p.m. on Jan. 3 that a metal box arrived at the drab, beige buildings that house the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center. Inside was a test tube packed in dry ice that contained swabs from a patient suffering from a peculiar pneumonia sweeping China’s central city of Wuhan. But little did Zhang know that that box would also unleash a vicious squall of blame and geopolitical acrimony worthy of Pandora herself. Now, he is seeking to set the record straight.

Zhang and his team set to work, analyzing the samples using the latest high-throughput sequencing technology for RNA, the viral genetic building blocks, which function similar to how DNA works in humans. By 2 a.m. on Jan. 5, after toiling through two nights straight, they had mapped the first complete genome of the virus that has now sickened 23 million and killed 810,000 across the globe: SARS-CoV-2. “It took us less than 40 hours, so very, very fast,” Zhang tells TIME in an exclusive interview. “Then I realized that this virus is closely related to SARS, probably 80%. So certainly, it was very dangerous.”

The events that followed Zhang’s discovery have since become swathed in controversy. Crises beget scapegoats and the coronavirus is no different. The floundering U.S. response to the pandemic has prompted a wave of racially tinged soundbites, such as “China virus” and “Kung Flu,” as President Donald Trump’s Administration seeks to divert blame onto the nation where the pathogen was first identified. “The outbreak of COVID angered many people in the Administration and presented an election issue for President Trump,” Ambassador Jeffrey Bader, formerly President Obama’s chief adviser on Asia, said at a recent meeting of the Foreign Correspondents Club of China.

Upon first obtaining the genome, Zhang says he immediately called Dr. Zhao Su, head of respiratory medicine at Wuhan Central Hospital, to request the clinical data of the relevant patient. “I couldn’t say it was more dangerous than SARS, but I told him it was certainly more dangerous than influenza or Avian flu H5N1,” says Zhang. He then contacted China’s Ministry of Health and traveled to Wuhan, where he spoke to top public health officials over dinner Jan. 8. “I had two judgements: first that it was a SARS-like virus; second, that the virus transmits by the respiratory tract. And so, I had two suggestions: that we should take some emergency public measures to protect against this disease; also, clinics should develop antiviral treatments.”

Afterward, Zhang returned to Shanghai and prepared to travel to Beijing for more meetings. On the morning of Jan. 11, he was on the runway at Shanghai Hongqiao Airport when he received a phone call from a colleague, Professor Edward Holmes at the University of Sydney. A few minutes later, Zhang was strapped in for takeoff and still on the phone—then Holmes asked permission to release the genome publicly. “I asked Eddie to give me one minute to think,’” Zhang recalls. “Then I said ok.” For the next two hours, Zhang was cocooned from the world at 35,000 feet, but Holmes’ post on the website Virological.org sent shockwaves through the global scientific community.

By the time Zhang touched down in Beijing, his discovery was headline news. Officials swooped on his laboratory to demand an explanation. “Maybe they couldn’t understand how we obtained the genome sequence so fast,” says Zhang. “Maybe they didn’t fully believe our genome. So, I think it’s normal for the authorities to check our lab, our protocols.”

Critics of China’s response have latched onto the Jan. 11 date of publication as evidence of a cover-up: why, they ask, didn’t Zhang publish it on Jan. 5, when he first finished the sequencing? Also, Zhang’s lab was probed by Chinese authorities for “rectification,” an obscure term to imply some malfeasance. To many observers, it seemed that furious officials scrambling to snuff out evidence of the outbreak were punishing Zhang simply for sharing the SARS-CoV-2 genome—and in the meanwhile, slowing down the release of this key information.

Yet Zhang denies reports in Western media that his laboratory suffered any prolonged closure, and instead says it was working furiously during the early days of the outbreak. “From late January to April, we screened more than 30,000 viral samples,” says Fan Wu, a researcher who assisted Zhang with the first SARS-CoV-2 sequencing.

And, in fact, Zhang insists he first uploaded the genome to the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) on Jan. 5—an assertion corroborated by the submission date listed on the U.S government institution’s Genbank. “When we posted the genome on Jan. 5, the United States certainly knew about this virus,” he says. But it can take days or even weeks for the NCBI to look at a submission, and given the gravity of the situation and buoyed by the urging of colleagues, Zhang chose to expedite its release to the public, by publishing it online. (Approached by TIME, Holmes deferred to Zhang’s version of events.) It’s a decision that facilitated the swift development of testing kits, as well as the early discussion of antivirals and possible vaccines.

Zhang, 55, is keen to downplay the bravery of his actions. But the stakes of doing what is right over what one is told are rendered far higher in authoritarian systems like China’s. Several whistleblower doctors were detained early in the pandemic. According to a Jan. 3 order seen by respected Beijing-based finance magazine Caixin, China’s National Health Commission, the nation’s top health authority, forbade the publishing of any information regarding the Wuhan disease, while labs were told to destroy or transfer all viral samples to designated testing institutions. Caixin also reports that other labs had processed genome sequences before Zhang obtained his sample. None were published.

It’s difficult to know what conclusions to draw. Dr. Dale Fisher, head of infectious diseases at Singapore’s National University Hospital, says he doesn’t think that any delay by the Chinese authorities was malicious. “It was more like appropriate verification,” he says. Fisher traveled to China as part of a World Health Organization (WHO) delegation in early February and says outbreak settings are always confusing and chaotic with people unsure what to believe. “To actually have the whole genome sequence by early January was outstanding compared to outbreaks of the past.”

Of course, Zhang’s fears based on the viral genome were just one evidence strut to inform China’s decision-making process, alongside public health data and clinical reports about specific cases. Despite mounting evidence of human-to-human transmission, including doctors falling ill, it was only on Jan. 20 that China officially confirmed community transmission. Two days later, Wuhan’s 11 million residents were placed on a bruising lockdown that would last for 76 days. Even while the WHO publicly praised China for transparency, internal documents seen by the Associated Press suggest health officials were privately frustrated by the slow release of information. One joint study by scientists in China, the U.K. and U.S. suggests there would have been 95% fewer cases in China had lockdown measures been introduced three weeks earlier. Two weeks earlier, 86% fewer; one week, 66% fewer.

Yet there was some historical basis for skepticism about the severity of the emerging viral disease. After all, the last global pandemic—the swine flu outbreak of 2009—was far less deadly than initially feared, mainly because many older people had some immunity to the virus, leading to criticism that the WHO was overly hasty and even overly dramatic in declaring a pandemic when the virology didn’t warrant it. “In China, even though we had a very bad experience with SARS and other diseases, in the beginning nobody—not even experts from China’s CDC and the Ministry of Health—predicted the disease could be quite so bad,” says Zhang.

Donald Trump disagrees. He has repeatedly claimed that swifter action by China could have stopped the pandemic in its tracks. “The virus came from China,” Trump said Aug. 10. “It’s China’s fault.” Beijing concedes that mistakes were made at the outset, though insists that blame lies solely with bungling local officials (who have since been punished for those failures), while the central government’s response was exemplary. This is, of course, its own politically motivated oversimplification. On both sides, wild accusations have eclipsed reason as Sino-U.S. relations spiral to an unprecedented nadir. While U.S. officials have suggested that COVD-19 originated in a Wuhan laboratory, their Chinese counterparts have propagated conspiracy theories that the U.S. military is responsible. “It’s not a good thing for China and the U.S. to be involved in this struggle,” says Zhang. “If we can’t work together, we can’t solve anything.”

Some facts are undeniable. The first U.S. case was confirmed on Jan. 21—a man in his 30s who had just returned from Wuhan to his hometown in Washington State. Japan confirmed its first coronavirus case one day later, and reported the world’s highest infection number early in the outbreak, before getting a handle on the situation. Today, the U.S. has 16,407 cases per million population compared with 462 in Japan. Across the world, authoritarian and democratic nations have both handled the crisis well and poorly.

For its part, the global scientific community has risen to the challenge, working across national boundaries to advance understanding of the disease, including priceless collaborations between Chinese and Western virologists. Previously, the best described epidemic in terms of viral genetics was the 2014 West African Ebola outbreak. Then, about 1,600 genomes were mapped over three years, providing insights into how viruses move between locations and accumulate genetic differences as they do. But for SARS-CoV-2, following Zhang’s initial genome, scientists mapped about 20,000 within three months. Genomic surveillance enables scientists to trace the speed and character of genetic changes, with ramifications for infection rates and the production of vaccines and antivirals. “Very large-scale genomic screening can evaluate whether any resistance mutations have occurred and, if they do, how those spread through time,” says Oliver Prybus, professor of evolution and infectious disease at Oxford University.

For Zhang, focus must now be on understanding how pathogens and the environment interact. Over the past century, an inordinate number of new viral diseases have emerged in China, including the 1956 Asian Flu, 2002 SARS and 2013 H7N9. Zhang attributes this to China’s diverse ecology and enormous population. Moreover, as China’s economy boomed its people have begun traveling far and wide in search of work, education and opportunities. According to the World Bank, almost 200 million people moved to urban areas in East Asia during the first decade of the 21st century. In China, 61% of the population lived in urban areas in 2020 compared with just 18% in 1978. This brings unknown pathogens and people without natural defenses into close proximity. “People and pathogens must be in contact [for outbreaks],” says Zhang. “If no contact, no disease.”

As urbanization intensifies, outbreaks of pathogenic diseases will only become more common. Mitigation, says Zhang, comes from deeper understanding of viruses, so that we can accurately map and predict which are likely to spill over into human populations. Just as satellites have made forecasting weather patterns unerringly reliable, Zhang believes science holds the key to predicting viral outbreaks with similar accuracy as with which we now anticipate typhoons and tornadoes. “If we don’t learn lessons from this disease,” says Zhang, “humankind will suffer another.”

Zhang Yongzhen Speaks Out About Controversies Around His Work | Time

***

Dr. Shahid Jameel

Shahid Jameel, eminent virologist and head of the advisory group to the Indian SARS-COV-2 Genomics Consortia (Insacog), resigned from his post on Friday.

Dr. Jameel confirmed to The Hindu that he'd quit but did not give any reasons for his departure.

Multiple scientists who are part of Insacog — a group of 10 laboratories across the country, tasked with tracking evolving variants of the coronavirus — told The Hindu that Dr. Jameel’s decision appeared to be sudden as he hadn't communicated reasons for his resignation to consortium members but one of them cited “government pressure” as a potential reason.

Dr. Jameel, who is Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences at Ashoka University, India, has been critical of aspects of the government's handling of the pandemic.

On May 13, in an invited opinion piece for the New York Times, Dr. Jameel summarised India’s response to the multiple waves and the uneven vaccination rollout and concluded by saying “scientists were facing stubborn resistance to evidence-based policy-making. On April 30, over 800 Indian scientists appealed to the Prime Minister, demanding access to the data that could help them further study, predict and curb this virus. Decision-making based on data is yet another casualty, as the pandemic in India has spun out of control. The human cost we are enduring will leave a permanent scar.”

The Insacog, setup in December, faced initial challenges with funds and equipment but since March has considerably accelerated sequencing samples from all over the country for variants. It has been tracking international variants of concern as well as discovered the so called 'Indian variant ' (B.1.617) that is believed to be instrumental in India’s devastating second wave.

Shahid Jameel quits as head of virus genome sequencing group - The Hindu

India’s DNA COVID vaccine is a world first – more are coming

The ZyCoV-D vaccine heralds a wave of DNA vaccines for various diseases that are undergoing clinical trials around the world.

ZyCoV-D is the first DNA vaccine for people to be approved anywhere in the world.Credit: Zydus Cadila

India has approved a new COVID-19 vaccine that uses circular strands of DNA to prime the immune system against the virus SARS-CoV-2. Researchers have welcomed news of the first DNA vaccine for people to receive approval anywhere in the world, and say many other DNA vaccines might soon be hot on its heels.

ZyCoV-D, which is administered into the skin without an injection, has been found to be 67% protective against symptomatic COVID-19 in clinical trials, and will probably start to be administered in India this month. Although the efficacy is not particularly high compared to that of many other COVID-19 vaccines, the fact that it is a DNA vaccine is significant, say researchers.

It is proof of the principle that DNA vaccines work and can help in controlling the pandemic, says Peter Richmond, a paediatric immunologist at the University of Western Australia in Perth. “This is a really important step forward in the fight to defeat COVID-19 globally, because it demonstrates that we have another class of vaccines that we can use.”

Close to a dozen DNA vaccines against COVID-19 are in clinical trials globally, and at least as many again are in earlier stages of development. DNA vaccines are also being developed for many other diseases.

“If DNA vaccines prove to be successful, this is really the future of vaccinology” because they are easy to manufacture, says Shahid Jameel, a virologist at Ashoka University in Sonipat, India.

India’s DNA COVID vaccine is a world first – more are coming (nature.com)

***

|

COVID-19 vaccine tracker Posted 03 December 2021 | By Jeff Craven Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society--

OWS: Operation

Warp Speed is a collaboration of several US government

departments including Health and Human Services (HHS) and

subagencies, Defense, Agriculture, Energy and Veterans Affairs

and the private sector. OWS has funded JNJ-78436735 (Janssen),

mRNA-1273 (Moderna), and NVX‑CoV2373 (Novavax), V590

(Merck/IAVI), V591 (Merck/Themis), AZD1222

(AstraZeneca/University of Oxford), and the candidate developed

by Sanofi and GlaxoSmithKline.

Authorized/approved vaccines

Showing 1 to 10 of 25 entries

|

COVID-19 vaccine tracker | RAPS

***

Share the link of this article with your facebook friendsFair Use Notice

This site contains copyrighted material the

use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright

owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance

understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic,

democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this

constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for

in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C.

Section 107, the material on this site is

distributed without profit to those

who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information

for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of

your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the

copyright owner.

|

|

|

|

||

|

||||||