www.aljazeerah.info

Nakba Survivors from Isdood, March 2013

Archives

Mission & Name

Conflict Terminology

Editorials

Gaza Holocaust

Gulf War

Isdood

Islam

News

News Photos

Opinion Editorials

US Foreign Policy (Dr. El-Najjar's Articles)

www.aljazeerah.info

Mohammed Tuman Hopes to be Buried in his Home Village, Isdood

By Asem Judeh

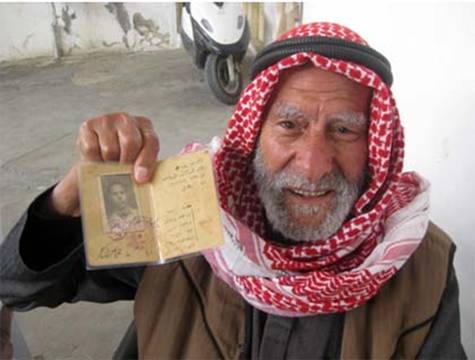

Mohammed (85) shows his ID card which was issued by the Municipality of

Isdod in 1947

Mohammed Mohammed Mohammed Tuman (85) was 19 years old when, on 20

December 1948, he and his family were forced to flee their home in Isdod,

now known as Ashdod. Victims of the Nakba (meaning ‘catastrophe’), they

fled along with their entire village of around 8,500 people. For some

time before, inhabitants of other villages had been arriving in Isdood

in their hundreds, bringing with them terrible accounts of the massacres

they had witnessed in places such as Qibya, Basheet, Deir Yassin, and

the Dahmash

Mosque.

No longer safe from the threat of attack by Jewish groups, with the

Egyptian army withdrawing from the area, some 30,000 people set out on

foot and walked for days until they reached relative safety.

Mohammed recounts his memories of the day his family was displaced from

their home: “We were so afraid that we would be killed. Already, 48

villagers had been killed, including my brother, Ahmed, who was killed

by Jewish settlers as he took part in the resistance. 15 more had been

taken prisoner. I kept a note of the name of every person who was killed

or imprisoned. I have that record still. On that day, my father sent me

to speak with the Egyptian commander, to ask him what they would do. I

could not meet him, but I spoke to an Egyptian soldier. I asked him,

“Are you going to stay and defend us, or withdraw?” He answered that he

did not know, but said that he would ask someone. By 4 o’clock that

afternoon, there were no soldiers left. The Jewish groups from the

nearby settlement of Nizanim were well-armed. They had weapons, tanks,

and warplanes. We had nothing. We had to leave.”

The journey south was arduous: “The whole village left, men, women and

children. My family and I were only able to bring a small amount of

flour to make bread and the clothes on our backs. We spent one night in

Hamama, another in Al-Majdal [now known as Ashkelon], and the third

night in Herbiya. We slept under trees, but we were scared of being

attacked. We had no food. Finally, on the fourth day of our journey, we

reached Khan Younis, where some friends of ours lived. Some of my family

had been scattered during the chaos, but eventually we gathered together

in Khan Younis. Our friends had a shelter made of straw that we were

able to live in. After some years, I built a house on the site. In all,

we lived there for fifteen years.”

Mohammed was newly-married, and struggled to start a new life with his

wife, Basima. “I found some agricultural work, but I only earned 10

piasters per day. At the time, that was the price of a kilo of sugar.

Our eldest daughter, Turkiyya, was born in 1949. My wife wasn’t well

enough to breastfeed her so we had to buy milk to feed her from a

neighbour who had a cow. My mother died the following year, when we were

still living in that straw hut. It was a hard and bitter life. Poverty

was widespread. I struggled to make enough money to provide for my

family through agricultural labour and selling some of the produce. My

hands were rough and cracked from using tools to work the land. We lived

in suffering for fifteen years, until UNRWA provided us with a shelter

in Khan Younis refugee camp in 1963, where we live still. The following

year, I began to work for a local family, who had a clothing business.”

Mohammed and his family were forced to flee the refugee camp for a brief

time during the Six-Day War of 1967: “We were very afraid. We moved to

the El-Mawasi area

near the sea and hid under the trees. After seven days, Israeli army

planes dropped leaflets instructing us to go back to the camp, carrying

white flags. We went back. However, I became jobless after the war. Our

standard of living was below zero. My wife’s sister and brother were

living in Lud, in Israel. They sent me a permit to join them and found

me a job as a labourer.”

After 20 years, Mohammed travelled north to the place of his birth: “When I arrived in Lud, I asked if they could bring me to see my village. When I saw Isdood, I was laughing and weeping – laughing because I was seeing my village once more, weeping because it was occupied. It was a mixture of feelings.” The Tuman family had been farmers and landowners, owning 120 dunums of land near the village before they were forcibly displaced. Mohammed had worked the land with his four brothers and their father. “As I wandered around, I found an old key on the ground. I recognised it as the key for starting the engine of the water well, which had since been stolen. I brought the key back with me to Khan Younis.”

Mohammed sitting before a map of Palestine which hangs in his home

Mohammed continued working in Israel until 1978: “At the time it was

very easy for Palestinians to travel to and from Gaza to work in Israel.

When my son, Turkiy, was old enough, he joined me there. Every two weeks

or every month, we came back to Khan Younis for a few days. I couldn’t

stay in Gaza where there was no work. I had a big family – four sons and

five daughters – and I had to provide for them. During that time, I

returned to visit my village, Isdood, many

times. Finally, after 20 years, I returned to Khan Younis and started a

shop.”

It is painful for Mohammed to speak of the more recent Israeli

offensives on the Gaza Strip, ‘Operation Cast Lead’ in 2008/9 and

‘Operation Pillar of Defence’ in November 2012: “All of Gaza was in

danger during those times and we were even more afraid than in previous

wars. Israel has a strong military force with modern weapons, shells,

and fighter jets. There was no safe place in Gaza. And I am an old man

now. I have been in this wheelchair for three years. I can do nothing to

resist the occupation.”

More than 64 years after Mohammed was forced to leave his home, he longs

to return to Isdood. “I still wish I could

return. If I could leave everything, every house that I stayed in since,

everything I have, I would leave it all. I was born there and I am so

attached to that place. The future of my nine children and my 42

grandchildren depends on our return to our home in Palestine. I hope I

will be buried in my home, Isdood.”

It is estimated that at least 700,000 Palestinians were forcibly

displaced from their homes during the Nakba of I948.

Under the operational

definition of the United Nations Relief Works Agency (UNRWA),

Palestinian refugees are people whose normal place of residence was

Palestine between June 1946 and May 1948, who lost both their homes and

means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict. The

descendants of the original Palestine refugees are also eligible for

registration. As of 1

January 2012, there were 4,797,723 Palestinian refugees registered with

UNRWA. 1,167,572 of them live in the Gaza Strip.

Under international law, all individuals have a fundamental right to

return to their homes whenever they have become displaced due to reasons

out of their control. The obligation of states to respect the

individual’s right of return is a customary norm of international law.

The right of return for Palestinian refugees specifically is affirmed in

UN General Assembly Resolution 194 of 1948, which “[r]esolves that the

refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their

neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable

date.” The resolution also provides that refugees who choose not to

return, or who suffered damage or loss to their property, should be

compensated by the responsible authorities.

Public Document

**************************************

For more information please call PCHR office in Gaza, Gaza Strip, on

+972 8 2824776 - 2825893

PCHR, 29 Omer El Mukhtar St., El Remal, PO Box 1328 Gaza, Gaza Strip.

E-mail: pchr@pchrgaza.org,

Webpage http://www.pchrgaza.org

|

|

|

|

||

|

||||||